Akwete: Weaving Heritage, Empowering Generations

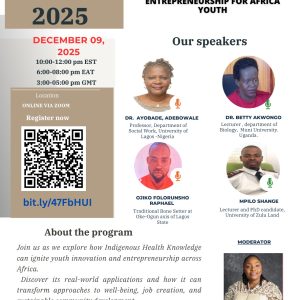

Indigenous Health and Well being: Opportunities for Jobs and Entrepreneurship for African Youth The Africa Indigenous Knowledge Research Network (AIKRN)

Indigenous Knowledge Systems at the Movies: Surviving with Games

Adeshina Afolayan

We usually think of games as means of entertainment. We are right. Have we ever connected them to our survival, or as a critical factor in survival? Not really. Then you have to watch the Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Games (2021, 2024). And then watch Tunde Kelani’s Agogo Èèwọ̀ (Taboo Gong, 2002). Both movies speak to different dimension of indigenous knowledge systems and the products they evolved as means of sociocultural cognition. It is however in Moana I & II (2016, 2024) that indigenous knowledge, sociocultural cognition and communal survival come together.

The Squid Game is very scary and troubling. Deaths. Killings. Deception. Injustice. It is a tragicomedy at its highest form. It has to be to become Netflix’s most watched series of 2021. You laugh at a point when adults are trying to master children’s games. And then the next, you are screaming with the characters when bullets tore into them. There are those of them who played these games and master them as kids. And there are those who never knew about them. And yet, their survival literally depends on winning those games. These were indigenous games that were probably scorned given the onslaught of, say, the video games. The group of five games—ddakji, biseokchigi, gonggi, paengi chigi and jegichagi—constitutes part of the traditional set of games that the indigenous Korean society bequeathed to the modern Koreans.

Their deployment in the Squid Game tells us two things. One, traditional games evolved as part of a general sociocultural dynamics that enabled the indigenous societies to not only entertain themselves but to also articulate a holistic framework of mental and physical health and wellbeing that tied games to human flourishing. Two, and most fundamental, Hwang Dong-hyuk, the film’s director, alerts us to the significance of drawing on the indigenous resources as a means of making culturally relevant films that speak our modern exigencies.

Drawing on indigenous resources is the stock-in-trade of Tunde Kelani, one of Africa’s most prolific filmmakers. The kind of terror that Tunde Kelani evokes is different from the one that suffuses the Squid Game. But the objective is the same: we will all neglect the indigenous to our collective detriment. Both Ṣaworo Idẹ (Brass Bell, 1999) and Agogo Èèwọ̀ deploy the motif of the tradition drum and gong as significant signifier of what the indigenous might be saying to the modern—or more precisely, how the indigenous has morphed into our current understanding of who we are and what we can achieve with what we have. Ṣaworo Idẹ opens with the beating of the brass-belled drum, and the inscription, “This is the parable of the drum as the voice of the people.” However, in Agogo Èèwọ̀, the filmmaker inserts a new dimension of children game songs, like the Kànnàkànnà song that is sung to the spinning of the yo-yo. Such songs not only provide light entertain for kids, but they also encode cultural wisdom on sociopolitical events and circumstances. Like the Jogbo society depicted in Ṣaworo Idẹ and Agogo Èèwọ̀, the song games of the children also form a critical part of the larger efforts at sanitizing such a society by relying on the indigenous cultural resources that would not have been considered effective. The song games inculcate in the children a sense of civic responsibility that enable them to guide and guard their rights and the well-being of their polity against those who would undermine their very existence.

Moana articulates an ancient Polynesian myth to tell the story of survival of a coastal village and her people. The beauty of the movie is that it allows us to see how traditional practices could both be entertaining and also enabling. The games are actually derived from the Polynesian and Samoan mythology, and they represent how these cultures navigate their complex realities, make meanings out of them while also enjoying themselves. The Eli le palai or “dig the yam”, for example, derives from the Samoan myth of origin—how Palai, the yam, offered to help Pili save his sister, Sina, from being eaten by Tuifiti the King of Fiji. Palai started growing from the ground and the people began harvesting it until the famine in the land was conquered. The entire storyline of Moana therefore effectively outlines a mythology of meaning, progress and survival—how a people tell their own stories to make sense of their indigenous knowledge, cognition and development.

But there is a larger point I am making. Films serve a larger and more fundamental avenues for making a case for the propagation of the significance of indigenous knowledge system and their multidimensional capacities to influence and inflect our modern existence. In the Squid Game, those who had played the traditional games as kids were able, at least, to momentarily survive, even though their survival was moderated by their greed which eventually led to their death. In Agogo Èèwọ̀, the song games tether the children to a sense of social responsibility. In Moana, the games are parts of a larger mythology of existence and survival. Thus, beyond conferences, essays, colloquia, and academic activities that have served as the mainstay of the advocacy for pushing the boundaries of Indigenous knowledge systems, the African Indigenous Knowledge Research Network (AIKRN) can articulate an even more effective strategy that requires a sort of partnership with recognized filmmakers across Africa. This partnership requires filmmakers whose cultural nationalist credentials could enable a viable and ongoing collaboration on not only the deployment of African Indigenous knowledge systems as a significant source of storytelling, entrepreneurship or existential survival and meaning making (in ways that will enable the filmmakers themselves to be aware of the dangers of simplifying their fundamental importance), but also an elaboration of their utility as means of making sense of modern exigencies and projecting into the future cinematically. The collaboration is also important as a vehicle for educating the society about how the indigenous resources of African societies could reorient our entrepreneurial and critical thinking capabilities, especially in a world of critical and competitive existential survival. Games require skills that affect both our cognitive function, cultural cognition and socioeconomic relevance and even progress.

Adeshina Afolayan, PhD

Professor of African Philosophy

Department of Philosophy

University of Ibadan

Nigeria

+234(80)-3928-8429

2023-2024 Founder’s Fellow,

National Humanities Center, Durham, US

Books/Philosophy and National Development in Nigeria (2018)/Fela Anikulapo-Kuti: Afrobeat, Rebellion and Philosophy (2022)

Edited volumes

Auteuring Nollywood (2014)/Palgrave Handbook of African Philosophy (2017)/Urban Challenges and Survival Strategies in Africa (2017)/Pentecostalism and Politics in Africa (2018)/Histories, Identities and Values in Postcolonial Nigeria (2020)/African Pentecostalism and World Christianity (2020)/Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Development in Africa (2020)/Pathways to Alternative Epistemologies in Africa (2021)/Global Health, Humanity and the COVID-19 Pandemic (2023)

Current Essays:

“On Critical African Philosophy” (2023)/“Pentecostalism, Anti-Clericalism and Post-secularism in Postcolonial Nigeria” (2023)

Essay on my philosophy

YouTube Presentation

My most recent essay

“Pentecostal Political Thought,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 2024

Indigenous Health and Well being: Opportunities for Jobs and Entrepreneurship for African Youth The Africa Indigenous Knowledge Research Network (AIKRN)

Indigenous Health and Well being: Opportunities for Jobs and Entrepreneurship for African Youth The Africa Indigenous Knowledge Research Network (AIKRN)

The Africa Indigenous Knowledge Research Network was created to undertake research geared towards identifying, re-centering and harnessing Indigenous knowledge in Africa.

©2026 copyright africaindigenousresearch.com